If the man kills by force using hands, knives and sticks, the woman kills with cunning using the tongue, poison and its derivatives. Poison (or “veneno” as it was a common voice in Dante’s time) comes directly from the Latin venènum, in connection with Venus, Venus, goddess of beauty and love. The venènum originally was therefore “every especially liquid matter, capable by its penetrating force of changing the natural property of a thing”. Poison has always been the favorite weapon of women because it causes an invisible death, atrocious and often without leaving traces. In reality, poison has also been widely used by men, who have made it the most suitable means to deflect suspicions and simulate a natural death. But Tofana water was an all-female poison.

It was also known as the Manna di San Nicola because contained in a bottle decorated with the image of St. Nicholas, a device to avoid arousing suspicion about the actual contents of the bottle, which has a whole history worthy of great respect. Tofana water spread throughout the peninsula was also known as Perugian water or Naples water. Without clearly being in favor of this activity, we think of the thousands of young and defenseless women who were married to elderly, violent, mostly rich men to settle their families of origin, in short, literally sold as sex objects and factories of heirs. For this reason, in some way, however murderer and seller of death, our Giulia Tofana becomes “a savior” and a heroine of the time “of all the unhappy unmarried women who often had to suffer violence to the point of death, which remained unpunished.

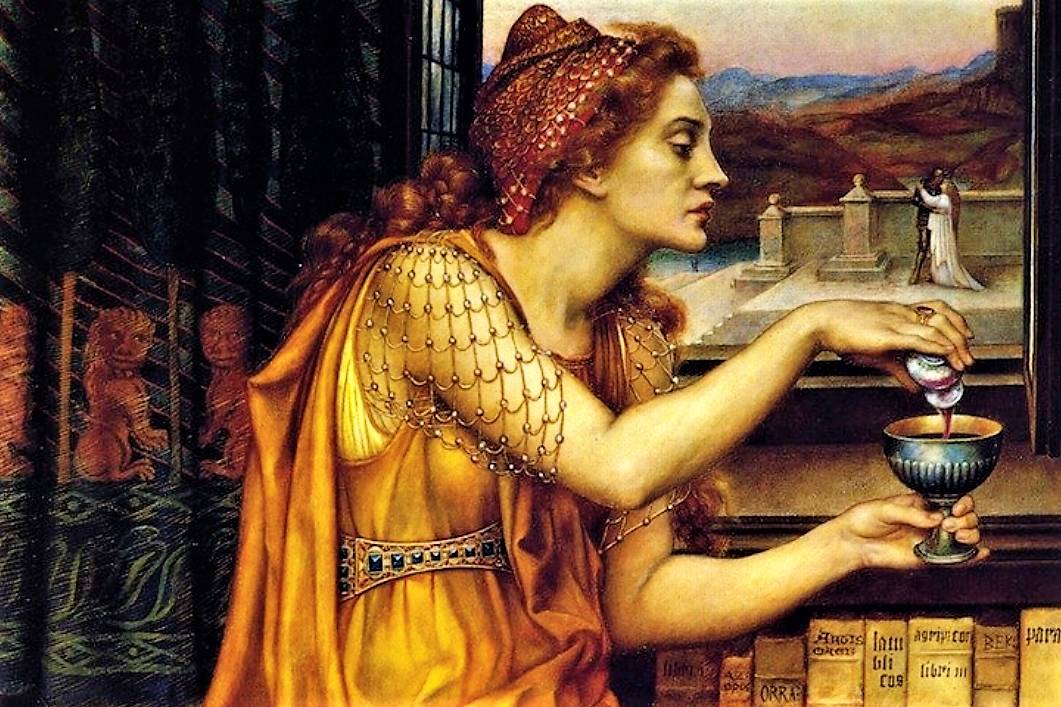

Giulia Tofana was a courtesan originally from Palermo who in 1640 who elaborated the recipe for the deadly potion. Colorless, tasteless and odorless, it was a deadly weapon with which to eliminate a person without arousing any suspicion, also because the effect was delayed for days and no one was able to trace death to anything other than a heart attack. A mixture of arsenic, lead and probably belladonna (the exact doses of each ingredient are unknown) mixed in boiling water and which killed without a trace. It was essential to pour a few drops a day to cause poisoning over time that would lead to an apparently natural death because it had no symptoms. Reading the writings of the doctor of Charles VI of Austria, the arsenic anhydride in the water created an acidic environment allowing the dissolution of lead and antimony, creating a highly toxic solution. During the Palermo period Giulia, already in the odor of inquisition due to a wife who had not followed the instructions of daily poisoning and therefore of a husband who unfortunately survived, had to move to Rome.

Maintained by a friar in a beautiful house in Trastevere, she continued her activity undisturbed, motivated not only by money, as she would later admit during the trial, by a feeling of justice and not of revenge to help poor women who, like her, had to sell one’s body: because “a marriage without love was in any case a form of involuntary, violent and chronic prostitution from which a woman could escape only with her own death”. A modern and undoubtedly unscrupulous woman who once again, in fact after years of “work” was now retiring, was “caught” again. One of her ladies acquaintances had told her about her husband’s violence, so he forced her to give her the poisonous product. The Countess of Ceri, in question, committed a gross but fatal mistake in this context: anxious to get rid of her husband, she used all the contents of the bottle, stirring up the suspicions of the relatives of the deceased.

It was clearly discovered and during the torture, admitted to having sold, most in the city of Rome, enough poison to kill 600 men, in a period between 1642 and 1651. In the year 1659 she was condemned and executed in Rome. , in the same place that the free thinker Giordano Bruno saw burn, that is in Campo de ‘Fiori. Bruno’s statue is not yours: why was she a murderer? In reality she was selling a poisonous potion, like someone who sells weapons, like someone who sells harmful medicines, only the latter are not condemned. It is clear, there were no mass media but the “comfortable” news spread even at the time, the homicidal madness crossed a long stretch of our peninsula, turned into fear and many women were accused by Tofana herself of having resorted to its poisons, were captured, tortured and publicly executed.

Others were strangled in the dungeons of buildings and walled up alive. The death of Giulia Tofana did not cause the stop of the water production that took her name, so much so that, between 1666 and 1676, the Marquise de Brinvilliers poisoned her father and two brothers before being arrested, in both directions, and executed.

The fear of contagion led to a real mass hysteria, and in Rome the idea spread that some women “possessed and of bad habits” used the deadly liquor of Giulia Tofana to pour it into fountains, wells, where there was some drinking water. Even the holy water fonts of the churches. Legend has it that no one entering the church dared to bathe their hand with holy water and one day, when the sacristan of the church of S. Lorenzo Damaso, the church of Giulia Tofana’s lover, saw a poor man dip his fingers to make the sign of the cross, began to shout to the greaser causing a lynching in the basilica by popular acclaim.

Until the mid-nineteenth century the memory of Giulia Tofana, and her potion, were so vivid that Dumas inserted a reference in the Count of Montecristo: “… we spoke lady of indifferent things, of Perugino, of Raphael, of habits, of customs, and of that famous Tofana water of which some, you were told, still keep the secret in Perugia ”. To be sadly famous, it seems that Mozart himself, speaking to his wife, told her that he would die poisoned by the Tofana water.